San Claudio al Chienti and the Romanesque churches with Greek crosses inscribed in squares in the Marche region. Lamusa Cooperative Society, Ascoli Piceno, 2006

Elisabeth de Moreau d’Andoy, Pievebovigliana, Piceno/Marche, January 2024

From the title, we know that Hildegard Sahler will date the monuments studied as Romanesque, despite her intensive use of the words "probably", "perhaps", etc. The Romanesque style begins in the year 1000.

Why is it important to date these buildings after the year 1000?

If they were built after the year 1000, they were not built by the Carolingians (around 688-900) and all the false history of the early Middle Ages that we are taught in universities and schools around the world remains standing.

Instead, if these buildings date from around the 8th-9th century, this confirms that Charlemagne had nothing to do with Germany, where there is no archaeological evidence.

Many important historians have supported this thesis: the Belgian Henri Pirenne (1862-1935), the Austrian Alfons Dopsch (1868-1953), the French Marc Léopold Benjamin Bloch (shot without reason by the Gestapo in 1944), the German Heribert Illig (1947-), the Italian Giovanni Carnevale (1924-2021), the Italian Gillo Dorfles (Ragazzi, Civiltà d’arte, vol. 2 2014, Atlas).

This is therefore a POLITICAL book.

I don’t intend to recap every mistake and political choice made by H. Sahler, but let’s look at a few.

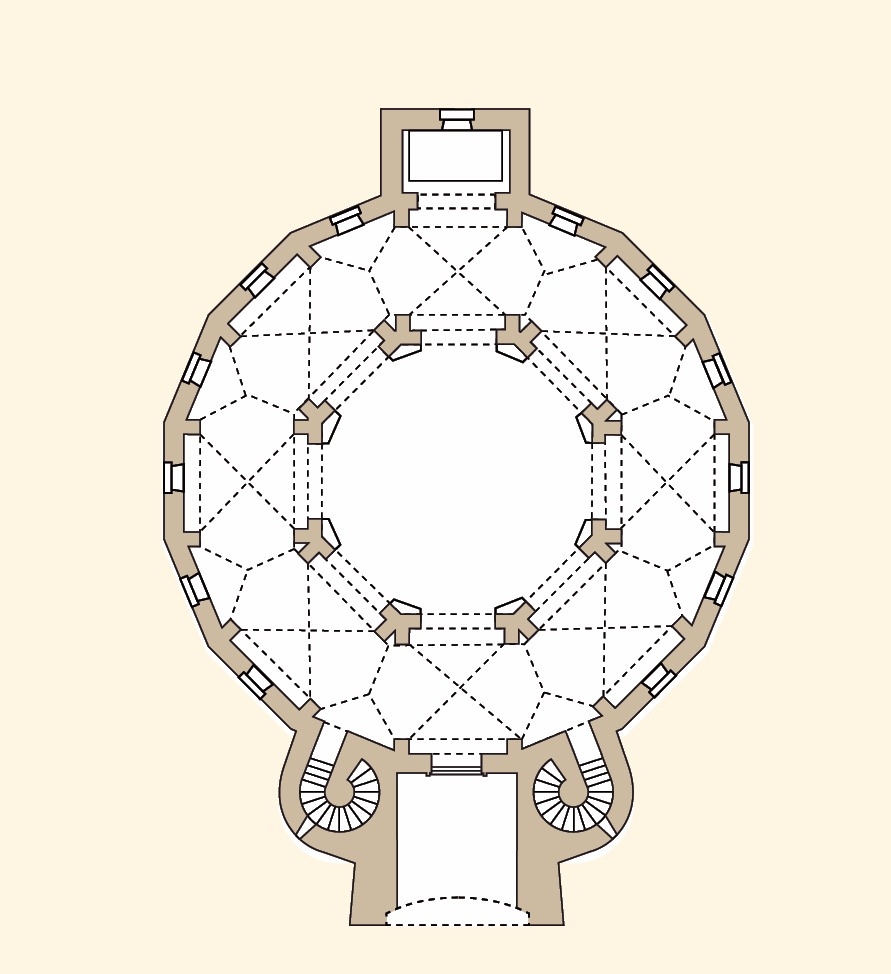

As luck would have it, H. Sahler does not include the plan of the “Palatine Chapel” of Aachen anywhere. Instead, this plan should serve as the model for a Carolingian chapels, to date the

churches she studies in the Piceno region.

Among the misleading chatter, Hildegard Sahler talks about 7 “churches” that are very important to our true history of the early Middle Ages. They have the same square plan, with 4 columns or pillars and apses. We will see in my conclusions why I put the word “churches” in quotation marks.

San Claudio al Chienti in Corridonia (Macerata)

Santa Croce di Conti in Sassoferrato (Ancona)

San Vittore alle Chiuse in Genga (Ancona)

Santa Maria alle Moje in Moje (Ancona)

Oratory of Théodulphe, a friend of Charlemagne, in Germingy-des-Prés (France)

Oratory of Rutbertus de Lozinga in Hereford (England)

Santa Maria in the castle of Paderna in Pontenure (Piacenza)

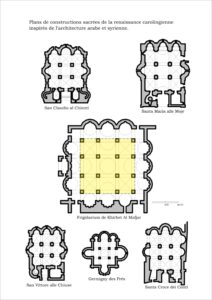

It was Giovanni Carnevale who discovered that these 7 buildings are clearly inspired/copied from the

Frigidarium of Khirbet-al-Mafjar in Syria.

The church of Santa Maria de Paderna, an astonishing smaller reproduction of the Frigidarium of Khirbet, is officially dated from the 9th century https://castellodipaderna.it/il-castello/.

H. Sahler does not openly contest the dating, but, by naming it in this group of monuments, she implies that it is Romanesque, that it was therefore built after the year 1000. In fact, she speaks of

this chapel on purpose to change its dating, obviously.

Santa Maria of Paderna

There are other monuments that should be included in this group of buildings. But H. Sahler is studying a small group that has close relationships with the Carolingians, in an attempt to prove that they are NOT Carolingians. Nevertheless, between the end of the Roman Empire and the year 1000, men continued to live, trade, build and create, particularly in the 8th and 9th centuries

(Carolingians). Architecture dating from several centuries before the year 1000 cannot be described as Romanesque.

How does H. Sahler date the buildings studied? She starts from the church of San Claudio al Chienti which, according to her, would be the first building of the group to have been built. She takes the first document we have which dates from 1030 and says, without proof, that it was certainly built around 1010 and is therefore Romanesque (11th century).

She then uses this invented reference point to date the other churches in the group.

And in fact, for each church studied, she devotes a chapter to “dating by stylistic comparisons”. That is to say, each time, based on the architectural similarities between these buildings, she attributes to the monument a date of construction similar to that of San Claudio, which she had made up.

Let’s say right away that there are doubts about the location of the church called San Claudio, in Corridonia. San Claudio was the name of the church in the now extinct Roman town of Pausolae.

Don Galiè’s research, with the help of georadar, revealed that Pausolae was located 1.5 km further towards Morrovalle than current San Claudio. Therefore, the current church was not originally called San Claudio. It was the Santa Maria chapel of Emperor Charlemagne. We can therefore imagine that the bishops of Fermo called Charlemagne’s chapel "San Claudio" in order to be able to usurp ownership at a time when the empire began to collapse.

By the way, San Claudio is not tetraconch as H. Sahler says throughout the book. It has five apses

and not four (tetra = 4 in Greek).

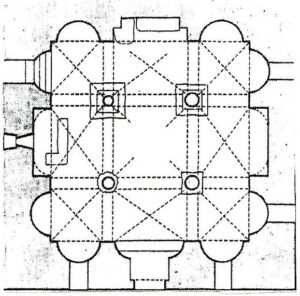

San Claudio

San Claudio

San Vittore alle Chiuse is also dated by H. Sahler to the 11th century.

There is a BUT. There are three stonemasons’ signatures discovered by Camillo Ramelli, 1852, p.3 et seq. All letters are capitalized. Camillo Ramelli dates the signatures to the 9th century. (i.e. Carolingian). Obviously Luigi Serra, the great destroyer of Marche archeology, then H. Sahler cast doubt on this dating. But in the third signature, there is a triangular point which, according to Deschamps (1929, p.55), has been used “since the time of the Carolingians”. Therefore, once again, this signature is dated to the 8th-9th centuries. Despite this, H. Sahler states that these dates are incorrect and that the signatures date back to the construction of the church, which is obviously the 11th century!

The square towers and monasteries/abbeys were built in the 12th and 13th centuries. It can be seen with the naked eye! The construction material is also different from that used to build churches. The towers and abbeys are therefore 2-3-4 centuries more recent than the “churches” themselves. But for H. Sahler, they were built at the same time as the churches. In doing so, H. Sahler transforms the “churches” into abbey churches even if, originally, the buildings studied were built isolated, independently.

In the case of Santa Croce dei Conti, this is downright ridiculous because the church was incorporated into an abbey centuries after its construction. In some places the exterior facade of the

church, with carvings representing the god Mithras, still exists in the abbey. If the church was built at the same time as the abbey, why does it have external facades within the abbey walls? There is also a clear difference in the construction materials between the church and the abbey.

Santa Croce dei Conti, original external facade of the church inside the abbey

I would also like to talk about the family of Counts Atto or Atti or Attoni who are of Burgundian origin, allied to the ancient Burgundian royal family. They became members of the Carolingian

imperial family through marriage. They were at that level. They had therefore inherited their properties in the Marches from the Carolingians. It was not, as H. Sahler says, a “local” family. Not

exactly.

Speaking of dating, we have Carolingian mausoleums in the same geographical area such as that of Rambona, dated around the year 895 by Professor Federico Guidobaldi of the Sapienza University of Rome, on behalf of the CNR. These mausoleums have the same general characteristics as the “churches” studied in this work. The tomb of Emperor Lambert was located in the Rambona mausoleum. It was destroyed on the orders of the bishop of Macerata, Vincenzo Maria Strambi.

The mausoleums of Carolingian families make it possible to date the “churches”, even without the bodies of the owners.

Thus begins to take shape a whole fabric of castles with their abbeys in which the owners of the castles had their own family mausoleum. As in neighboring Croatia. The imperial churches that H.

Sahler studied without understanding the rest of the picture are part of this fabric.

Read the “Mausoleum-crypts” page on this site.

Next we have the representation of the owner of the Santa Croce dei Conti church in Sassoferrato.

On the first capital of the pillar on the left as you enter: it’s Charles Martel, Charlemagne’s grandfather!

H. Sahler pretends not to have recognized Charles Martel who is represented with all his attributes, including the dead bear next to him, when he was a child. The stonemason’s workmanship is typical of the 7th-8th century.

If she or anyone else recognizes this, the whole map construction of false early medieval history collapses. Charlemagne has nothing to do with Germany/Aachen where there is no archaeological

evidence.

I am a Belgian. Our family castle, Andoy where I was born, is not far from the birthplace of Charles Martel. He was born around 680-90 in Andenne in Belgium between the towns of Liège and Namur, on the banks of the majestic Meuse. It is Charles Martel, grandfather of Charlemagne, who is represented on a pillar capital in the church of Sassoferrato in the Piceno region, with all his

attributes.

Andoy, Belgium

Charles Martel, Santa Croce dei Conti, Sassoferrato, Italy

For H. Sahler, it’s Saint Daniel in the lions’ den. Where are the lions?

We have two authentic documents which state, separately, that the oratory of Théodulf of Orléans, friend of Charlemagne, at Germingy-des-Prés (France) and the oratory of Rutbertus de Lozinga at Hereford in England were copied on the Palatine Chapel of Charlemagne.

The 2 chapels are square in plan and very similar to the chapel of San Claudio al Chienti. This puts the octagonal “Palatine Chapel” of Aachen out of the picture. QED.

H. Sahler does not talk about these documents.

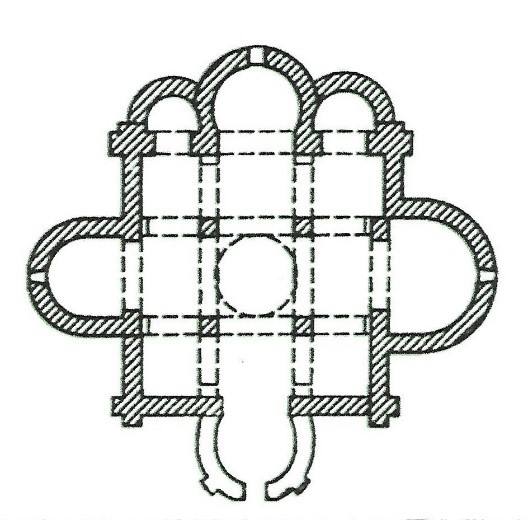

Germigny-des-Prés, France. Plan of Theodulf’s square oratory copied from Charlemagne’s chapel

The front apse was added in 1867

Aachen, Germany, “palatine chapel” of Charlemagne

Does it resemble Théodulf’s oratory at Germigny-des-Prés?

H. Sahler also ignores the discovery in 1926 of the tomb of Emperor Otto III in the church of San Claudio al Chienti, in front of the altar. The emperor’;s body had been on public display for a week before being reburied. Enzo Mancini’s grandfather, in the sources below, was an eyewitness.

According to the pamphlet “Gone with the Wind in the Vatican”, the emperor’s remains were then sold and paid for 7 billion Italian lire in Switzerland.

The remains of Charlemagne’s elephant, Abul Abbas, were found in a field in San Claudio.

These are two well-documented events, never reported to the superintendency.

As usual, the tombs are looted and then destroyed. All valuables are stolen and sold. The emperor’s jawbone was dismantled and sold, one tooth at a time. Who knows if his long blonde/red hair was sold in strands.

CONCLUSIONS

We know from Einhard and Notker that King Pepin had Syrian architects and workers imported.

There was a Syrian architect at Charlemagne’s court: Abdullah.

The buildings studied were built for the Carolingians and therefore belonged to them.

They were built as independent buildings.

They were used by the Carolingians for their activities.There is no room for a large public inside.

No public baptismal font testifying to parish rights dating from the same period has been found in these churches.

To give credence to his theory that these buildings were abbey “churches”, H. Sahler continually speaks of “naves”. But if these buildings are square, there are no naves. There are spans. See the

definition of nave in the dictionary.

What were these monuments used for? I think the Carolingians were practical people. These buildings were used for religious and court rites, such as the coronation of emperors, but also for the

administration of justice. They served in the imperial administration and religion was part of it.

We have various testimonies according to which Charles Martel administered justice. Charlemagne was available to the people for their legal grievances.

Charlemagne had his private property in the Piceno region. The Capitulary of Villis describes it.

It had its palace, its chapel, its capital and its military camps: Camp de Mai (Campo Maggio) and Camp Long (Campo Lungo) which still exist today as toponyms around San Claudio. al Chienti,

TODAY.

Charlemagne was born and died in the Piceno region.

• Sources

– Giovanni Carnevale, La scoperta di Aquisgrana in Val di Chienti, Queen Editore, Macerata, 1999.

– Hamilton, R.W. and Grabar, Khirbet al Mafjar, Oxford, 1959.

– MiljenkoJurković. Bertelli, Carlo and Brogiolo, Gian Pietro and Jurković, Miljenko and Matejčić, Ivan and Milošević, Ante and Stella, Clara, Bizantini, Croati, Carolingi. Alba e tramonto di regni e

imperi, Milano, Skira Editore, 2001, p. 151 et following pages.

– Mancini, Enzo, Aquisgrana Restituta, Macerata, published by the author with a contribution é par l’auteur with a contribution from the Municipality of Corridonia, 1997.

– Tomb of Emperor Otton III destroyed. Pamphlet: I millenari, Via col vento in Vaticano, one can download in PDF on Internet.

– Tomb of Emperor Lambert destroyed: Un segreto di pulcinella: article signed by Antonella Ventura, published in the journal Emmaus, year XXVII, n. 16 dated 21 April 2012.

See article Elisabeth de Moreau d’Andoy, Mausoleums-crypts, 2016.

– Sarcophagi at Sant’Angelo in Montespino destroyed: local historian Onorato Diamanti found his historical sources in the Papiri Pievano Pacifico, Inventory 1848 at the archives of the Church of

San Michele Angelo, Montefortino.

Diamanti, Onorato, Inediti Fortinesi, Montefortino, Published by Centro Studi Fortunato Duranti,

1998, p. 88-91.

– Tomb of Queen Berterada, Charlemagne’s first wife, destroyed (photo): Elisabeth de Moreau d’Andoy, Charlemagne the Dark Secret, Amazon, 2015.

– Imperial Mausoleum of Santa Maria Piè di Chienti destroyed by Luigi Serra: Serra, Luigi, L’arte nelle Marche: dalle origini cristiane alla fine del gotico, G. Federici, Milan, 1929.

– Illig, Heribert, Hat Karl der Grosse je gelebt? Graefelfing, Mantis Verlag, 1994.

Das erfundene Mittelalter, Düsseldorf, Econ Editore, 1996.

– Pirenne, Henri, Maometto e Carlo Magno, Rome, Newton Compton Editori, 1997.

– Galiè, Vincenzo, Ecco a voi il sito et la forma dell’anfiteatro romano di PAUSULAE. La città, quindi, era nelle immediate vicinanze, Litografia COM coop, Capodarco di Fermo, 2011

– Galiè, Vincenzo, La città di PAUSULAE e il suo territorio, Biemmegraf, Macerata, 1989